Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality around the world.1 The 2014 U.S. Surgeon General’s Report found that smoking is a cause of type 2 diabetes; hence, smoking cessation in this population warrants attention due to its significant impact on the underlying disease.1–3

Smoking and its association with diabetes risk

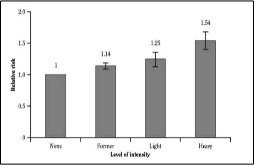

Clinical evidence suggests that smoking increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes; the risk is approximately 30% to 40% higher for active smokers than for non-smokers.1 A meta-analysis that explored the dose-response relationship between smoking and the development of type 2 diabetes found that the risk was 54% higher (RR 1.54; 95% CI: 140–1.68) in heavy smokers (those who smoked ≥20 cigarettes per day) and 25% higher (RR 1.25; 95% CI: 1.14 to 1.37) in light smokers (those who smoked 0 to 19 cigarettes per day), relative to non-smokers.1 Former smokers remained at an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes as well (RR 1.14; 95% CI: 1.09–1.19), but their risk was lower than that of light and heavy smokers (Figure 1).1

Similarly, a meta-analysis of 25 prospective cohort studies assessed the association between active smoking and incidence of type 2 diabetes in 1.2 million patients.4 The risk of type 2 diabetes was increased by 61% for those individuals who smoked an average of one pack per day. When compared with non-smokers, the risk of developing diabetes for lighter smokers increased by 29%, similar to the increased risk found in former smokers (23%).4

Smoking and glycemic control

Smoking has been associated with poor glycemic control and the development of diabetes-related complications.5 The mechanism by which smoking increases glycated hemoglobin (A1C) may relate to the aggravation of insulin resistance in people with type 2 diabetes.4 Epidemiological studies associate smoking with reduced insulin secretion.5 Nicotinic receptors are found on pancreatic islet and beta cells; it has been hypothesized that nicotine might reduce the release of insulin through neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on islet cells.5 Furthermore, while smokers tend to be leaner than non-smokers, many epidemiologic studies have shown that smoking is independently associated with a risk of central obesity.6 Central obesity is a well-established risk factor for insulin resistance and diabetes.7

Smoking and microvascular and macrovascular complications

Microvascular complications in diabetes are linked to metabolic control.8,9 Smoking has the potential to increase the risk for retinopathy and macular degeneration in individuals with diabetes, through its association with poor glycemic control, hypertension and effects on vasculature. There is some evidence from epidemiological studies to suggest an increased risk of the development of neuropathy and its progression in individuals with diabetes who smoke.10,11 Smoking is also a documented risk factor for both the development and progression of various types of neuropathy. In individuals with diabetes who smoke, the risk for renal disease is 2 to 3 times higher than that of nonsmokers.12 Evidence suggests that smoking promotes the progression of renal disease in type 2 diabetes.12 Some of the proposed mechanisms by which smoking is thought to harm the kidneys include:

- Increased blood pressure and heart rate

- Reduced blood flow in the kidneys

- Increased production of angiotensin II

- Narrowing of the blood vessels in the kidneys

- Damaged arterioles

- Arteriosclerosis of the renal arteries

- Acceleration of the loss of kidney function

Individuals with diabetes who smoke are also at an increased risk of macrovascular complications,13 related to the effects of smoking on the vascular and hemostatic systems.12 Smoking is associated with a threefold increase in the risk of myocardial infarction and a 30% increased risk of stroke. In addition to being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease, smoking has an unfavourable effect on the lipid profile, increasing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol while lowering high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Helping them quit: the 3A’s

Clearly, it is important to assist patients with diabetes to quit smoking and, as with all smokers, the combination of pharmacotherapy and support is the most effective strategy14

Brief interventions into tobacco use have been shown to increase the chances of smoking cessation.15 One approach that can be used is Very Brief Advice on Smoking – 30 Seconds to Save a Life (Figure 2).

ASK: Establish and record smoking status for all patients

- Are you a smoker?

- Do you still smoke?

- How are you doing with not smoking?

ADVISE: Advise patients how to stop

- Advise patients that the most effective strategy for smoking cessation is a combination of support and pharmacotherapy.

- Take the opportunity to advise patients to stop smoking when they are visiting you for any health concern.

- It is important to acknowledge that most smokers relapse several times before achieving long-term success, and that relapse is a learning opportunity and not a sign of failure.

- Do not simply advise the patient to stop smoking, as this immediately puts the smoker on the defensive, which is not an effective use of time.

ACT: Offer help

- If you are not able to provide counselling yourself, refer the smoker to a smoking cessation counsellor where possible (community pharmacy-based program, smoking cessation clinic, public health unit, smoker’s helpline/quit line, group counselling, internet programs, websites).

- When faced with an offer of support and assistance – not instructing, nagging or advising – many patients (even those who were not thinking about making an immediate quit attempt) will respond positively.

Summary

Smoking increases the risk of type 2 diabetes and is associated with poor outcomes of the disease. For individuals with type 2 diabetes who smoke, it is more difficult to achieve targets for glycemic control, and the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications is increased. Healthcare providers can help these individuals quit smoking using the simple and brief 3A’s approach.

References

- US Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking – 50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress/. Accessed April 6, 2016.

- Sherman JJ. The impact of smoking and quitting smoking on patients with diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2005;18:202–208.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Diabetes. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/sgr/50th-anniversary/pdfs/fs_smoking_diabetes_508.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2016.

- Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, et al. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298:2654–2664.

- Yoshikawa H, Hellström-Lindahl E, Grill V, et al. Evidence for functional nicotinic receptors on pancreatic beta cells. 2004;54:247–254.

- Kaufman A, Augustson EM, Patrick H, et al. Unraveling the relationship between smoking and weight the role of sedentary behavior. J Obes. 2012;2012:735465.

- Westphal SA. Obesity, abdominal obesity, and insulin resistance. Clin Cornerslone.2008;9:23–29.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;977–986.

- United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Intensive blood glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837–853.

- Sands M, Shetterly SM, Franklin GM, at al. Incidence of distal symmetric (sensory) neuropathy in NIDDM: the San Luis Diabetes Study. Diabetes 1997;20:322–329.

- Tesfaye S, Chaturvedi N, Eaton SE, et al; EURODIAB Prospective Complications Study Group. Vascular risk factors and diabetic neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:341–350.

- Eliasson B. Cigarette smoking and diabetes. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;45 405–413.

- Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes. 2013;37(suppI1):S1–S212.

- Stead LF, Koilpillai P, Fanshawe TR, et al. Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD008286.

- Aveyard P, Begh R, Parsons A, et al. Brief opportunistic smoking cessation interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare advice to quit and offer of assistance. Addiction. 2012;107:1066–1073.